Small programming faults can overflow an entire system

Many years back, in a different company… My company had been doing a shift toward the use of Service Oriented Architecture for the past few years.

In this context, we built a micro-service A that maintained a view on some financial information. The goal was to asynchronously create a data representation that offered better performance for some very common query patterns we had.

At the time, we had been testing the service extensively. We had a demo coming the next days, to show all the progress that we had made.

The code had not changed since the last tests we made. Still, we decided to make a last run of the demo. And it failed miserably. The same test case as before failed. The system was not even responsive.

The error that threw the entire system astray turn out to be ridiculously small.

The context

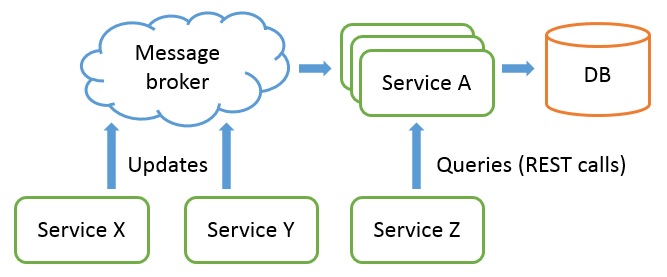

Our service A was a stateless service, fed by a message broker to receive a feed of real-time updates (from services X and Y below).

Its goal was to aggregate asynchronously these updates and serve queries to other services (service Z below) via a REST API:

The goal of the demo was to trigger an update on service X (via GUI interactions) and show that it correctly updates the view maintained in the service A (again via GUI interactions).

Technically, it was meant to demonstrate that service X correctly sends update messages to service A and that our new service A correctly processes them, and importantly processes them faster than the previous implementation as a monolythic service.

Following the log trail

But our service that was so quick to react in our previous tests now was apparently completely irresponsive. Or was it?

The symptoms

After a quick investigation, it turned out that our service did not crash. In fact, it would still service queries! But the queries would return data that remained invariably stale, and so the GUI was not changing, giving us the impression that the service was dead.

In reality, all services were running, but the view maintained by the service A was not impacted by GUI updates performed on service X.

The rules of the 4 Rs

We naturally tried the rules of the 4 Rs: Retry, Restart, Reboot, Re-deploy… but it did not clear the error away. Not this time. Something was stuck, something that was not in the transient memory of the services.

So we started to look into the logs to identify the guilty service.

Producer or consuner fault? Neither…

We first looked into the log of the service X, hoping to find why it did not send any update messages to service A. Instead, we found that the service X did correctly send the messages.

We then looked the logs on the consumer side, hoping to find why the service A did not receive or process any of the messages. Instead, we found that the service A was being overwhelmed with tons of messages from the broker, conveying updates of service X.

Looking these messages in details, to our surprise, they all looked the same! The service A was in fact consuming tons of update messages (several hundreds per second), but these messages were always the same ten or so.

Maybe a message acknowledgment issue? No…

Our next hypothesis was that our service was not correctly acknowledging the messages it received. In such case, the message broker would always serve the same messages over an over again.

We verified the logs of the service and it was not the case: it was correctly acknowledging the messages sent to it. Digging deeper, it was also clear that the broker was correctly dropping these messages after receiving the acknowledgment and not serving them again.

Back to the emitter (service X), we made sure that it was not sending those updates over and over. But no, it was doing the correct thing: one update, one notification message.

So which services was responsible to send those messages to the message broker?

Looking for the guilty emitter

Something, somewhere, must have been sending these same messages over and over again. They are not appearing out of thin air.

At this point, we decided to proceed by elimination.

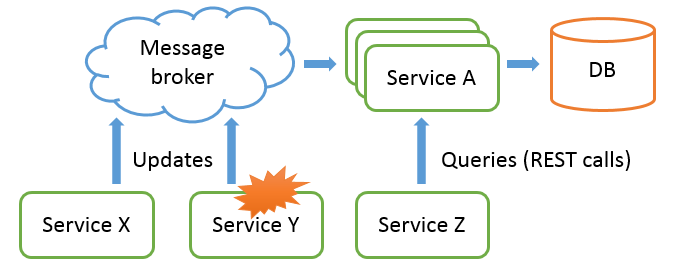

We stopped, one by one, each and every service that could possibly send data to the service A through the messaging system, until we noticed a reduction of the traffic. And so we found the guilty service: it was service Y.

Once Y was shut down, we saw the queue being slowly consumed by service A. A few minutes later, the whole garbage was gone. And finally the update of service X was processed.

It’s all clear now!

Now at that point, we could finally understand why our service A had not been very responsive to any updates during our demo rehearsal. It was actually responsive but was instead completely overwhelmed by the traffic it was facing. The resulting latency was so high that the service was not able to react to these updates in real-time.

It was clear why the error first looked like a lost update issue. Because the service had been built with an idempotent business logic, the 10 repeating messages that were flowding the system had no observable effect other than overwhelming the service.

And because the service had separate thread pools for processing updates and serving queries (which is a good design principle called the bulkhead), the query side was still responding with stale data.

Debugging the Sweeper service

Now, time to understand why service Y suddenly started to flood the messaging infrastructure with a continuous flow of identical messages. First, we have to understand what service Y is for.

Sweeping unsent messages

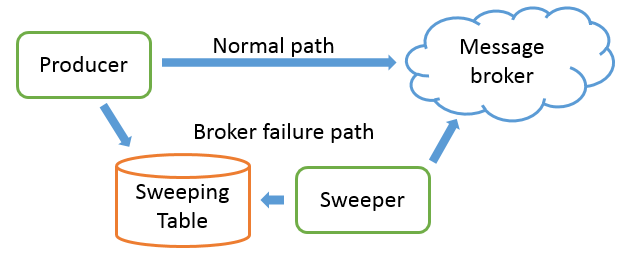

The service Y, guilty of flooding the messaging system, was a technical service acting as a Sweeper. Its goal was to make sure that messages that could not have been sent to the message broker (because the broker was not alive at the time or not reachable) would eventually be sent to the broker when it would come back online.

Basically, any service wanting to send a message to service A (or any other service) through the message broker, would first need the messaging infrastructure (the message broker) to be alive. But would the broker be down, we could not afford to halt all services.

So instead, the transmitting service, service X in our case, would fall back to writing the message in the Sweeping table, a table stored in database (1).

The Sweeper task was to poll periodically the sweeping table, to fetch and transmit these messages that could not have been sent and remove those messages from the sweeping table after successful transmission.

(1) The Sweeper can have another role as well. By writing in the sweeper table inside a DB transaction local to the transmitting service, this pattern allows to make sure we only send messages if the rest of the commit was successful (a useful pattern if the transmitting service has to write in his own DB and wants to make sure an update is sent if and only if this commit is successful).

Digging into the Sweeper code

In principle, the code of a Sweeper is really simple. It regularly polls the sweeping table, fetch the unsent messages, sends them, wait for the acknowledgment of the message broker, and then mark these messages as being sent (we marked them as sent after acknowledgement for guaranteed delivery (2)).

In our case, the code was written in Java, and roughly looked like this:

private void pollSweeperTable(Session session) {

List<Message> unsentMessages = messageRepository.fetchUnsentMessages();

for (Message message : unsentMessages)

sendMessage(session, message);

messageRepository.markSent(unsentMessages);

}

- The load and save of unsent entries is done using JPA (via the message repository of JPA)

- The messages are sent using JMS (the

Sessionobject passed as parameter of the function)

These might seem as details, but they are not. The failure mode of our APIs are often what makes the difference in how a failure propagate in our system.

(2) And yes, as you have guessed, this means you can have double transmission, as often in distributed systems. So the the receiver of messages must do deduplication or be idempotent or else this pattern is dangerous to use.

JPA saving errors

It turns out that when JPA tries to save an object, it throws an exception if the ID of the object is not unique in the table. Basically, JPA uses the ID to know which record to replace, and does not know which one to replace, so it panics.

The overall incident started like this: one service managed at some point to corrupt the Sweeping table. The direct consequence was that two messages now shared the same ID in the sweeper table (yes, there should have been a unique index, we will come back to that).

So when the sweeper encountered these messages, it managed to load them, send them, but failed to save them, marked as “sent” for there were two messages with the same ID. So the next sweeper loop would load the same two messages, send them again, and fail to save them again.

Basically, we got an infinite loop sending the same messages over and over again.

Interacting with transactions

This infinite loop does not yet explain everything. There were 2 corrupted messages. Why are there 10 messages being sent repeatedly instead of 2?

A quick look at the code gave us the answer: the sweeper marked all the messages as sent in the same DB transaction. Therefore, a single corrupted message makes the whole transaction fails.

private void pollSweeperTable(Session session) {

List<Message> unsentMessages = messageRepository.fetchUnsentMessages();

for (Message message : unsentMessages)

sendMessage(session, message);

messageRepository.markSent(unsentMessages); // One DB transaction

}

As a consequence, instead of just sending the two corrupted messages over and over again, the Sweeper sends all the unsent messages of the Sweeping table over and over again. And guess what? There were about 10 messages in the sweeping table during the incident.

Note: This behavior was motivated by performance. Marking all the messages as sent inside a single commit limits the impact on the database. It was an interesting bet knowing that sending the same messages twice – occasionally – is not a problem: idempotent receivers were already needed by the “at least once” guarantee of our messaging infrastructure.

Here comes the pokemon catch

To finish up, there was a last issue that made everything much much worse. The Sweeper iteration loop was surrounded by a wonderful Pokemon try-catch, logging and swallowing all exceptions:

try {

pollSweeperTable(Session session);

// …

} catch (Exception e) {

// Log the exception

}

For sure, not swallowing the exception would not have solved the issue. The Sweeper would have crashed upon marking the messages as sent, and then would have been revived by the supervisor, and then would have sent the messages again before crashing again.

The sweeper would still have flooded the messaging system. But it would have shown on the monitoring. Instead, absorbing the exception made the identification of the root cause of the system failure much less obvious. The first visible sign was another service that stopped responding.

What lessons is there to be learned?

Dealing with errors, not anticipating them

Distributed systems are a weird beast. We cannot anticipate most errors in a distributed systems. As illustrated here, some errors are not even necessarily symmetric.

We may be able to connect to the DB to load a record, but not to save the record, the same way that we may be able to send a message through a network link but not receive an answer. Some errors are out of our control (another service corruption our DB in our case).

Therefore the important thing is to put in place mechanisms that limit errors from propagating and lead to a system failure, and try to detect and report these errors as soon as possible.

Dealing with the errors that we anticipated, and pokemon catching the other cases, is a recipe for incidents such as this one.

The way to fix it

In that case, a number of different things would have helped.

First, adding a unique index on the sweeper table to prevent corruption of the message IDs and identify the source of the corruption (at the time of writing, we did not find it).

We customized our JPA repository to use a JQL update where request. Now, whenever there are messages with conflicting IDs in the sweeper table, both duplicates will be marked as “sent” (we will lose a corrupted message instead of losing the entire system):

@Modifying

@Query(

value = "update SweeperTable set sent = 1 where messageId in (:messageIds)",

nativeQuery = true)

void markSent(@Param("messageIds") List<Long> messageIds);

Adding back-pressure on the broker message queue, so that we get clear overflow errors when the situation gets out of control.

And of course remove the Pokemon catching try-catch block ;)

Comments