Distributed agreement on random order: Lamport Timestamps

If we succeed in this task, we will have succeeded in building what easily qualifies as one of the world most wasteful way to random shuffle. We now have a stupid task to do, and a perfect architecture to do it. We just miss the perfect language for the task…

It is quite astonishing that some very simple algorithms are able to solve what seem to be very complicated problems. Take the ordering of events in a distributed system.

We cannot accurately synchronize clocks between several devices. And yet, there is a simple and beautiful algorithm which allows to define a total ordering on the events occurring in these devices: Lamport timestamps.

Today’s post is dedicated to illustrating this algorithm through a simple (and arguably completely absurd) example, all implemented in Elixir.

Ordering events in a distributed system

Say we want to process a bunch of event in a distributed system which works in a multi-leader setting:

- There are several nodes of the cluster on which we can process events

- Event are processed and request are answered before every other leader is notified

- Leaders asynchronously notify of these events to all the other nodes

We would like all the nodes of the cluster to eventually agree on an total order on the events, a total order that is consistent which what actually happened in the system (i.e. that makes sense in terms of causality):

- For two events E1 and E2 on the same node, if E1 was processed before E2, all nodes must agree that E1 happened before E2

- For two events E1 on node N1 and E2 on node N2, if N2 had knowledge of E1 (via notification from N1) when E2 was processed, all nodes must agree that E1 happened before E2

The Lamport timestamps algorithm (also known as Lamport clock) is an astonishingly simple and clever algorithm that gives us just that.

Lamport timestamp algorithm

The algorithm itself is very simple to follow. It only requires each node to maintain a counter (also known as a logical clock) and update it as follow:

Upon receiving an event E on node N:

- Increment the logical clock of the node

Clock(N)by 1 - Log this event E with

Time(E) = Clock(N)andOrigin(E) = N

To send a replicate of an event E that occurred on node N:

- Send the full log of the event E with its time

Time(E)and originOrigin(E)

Upon receiving a event log replica E with Time(E) and Origin(E):

- Update the logical clock of the receiving node

Clock(N)to:1 + max(Clock(N), Time(E))

After a while, all nodes will have the same event logs. At this point, to retrieve an ordered history of the events, we just need to ask any node for its log of event, and sort them by their time and then their origin.

Note: For a more detailed description of the algorithm and its not-that-obvious implications in terms of ordering and capture of causality, you can refer to Wikipedia or better, look at the original publication.

Absurtity begins - Shuffling a sentence using Lamport timestamps

As explained earlier, Lamport timestamps allow us to totally order a sequence of event in a distributed multi-leader system, in such a way that it respects causality. We will consider the specific case of such a system to illustrate the algorithm.

A wasteful way to shuffle

For the rest of this post, we will build a simplistic distributed multi-leader in-memory buzzword compliant data store, where events being processed are insertion commands. We will insert in this data store all the words of a given sentence, distributing our writes evenly among its different nodes.

We will then demonstrate how Lamport timestamps make sure that our nodes eventually agree on the order of word insertions in the system.

Now, if our nodes agree on an order of insertion of the words of a sentence, they agree on the order of the words of the sentence. In other words, and thanks to Lamport timestamps, the nodes of our distributed in-memory data store will eventually agree on a given random shuffling of the words of the sentence.

If we succeed in this task, we will have succeeded in building what easily qualifies as one of the world most wasteful way to random shuffle – and without any good random properties built-in.

Yes, this is absurd. But also quite fun.

Architecturing the mess

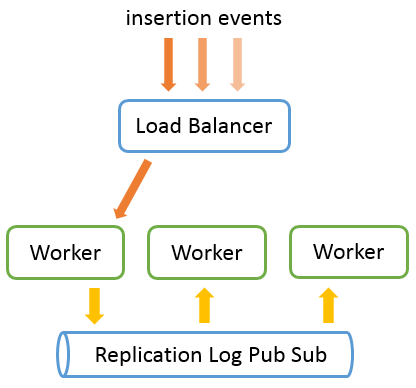

To build our eccentric random shuffler, we need a bit of infrastructure. In addition to our N database replicate (which we will call workers), we will need:

- A load balancer: to dispatch the insertion of words among our workers

- A pub / sub messaging system: to replicate the logs of one node to other nodes

This is how it will work. We will send all our insertion request through the load balancer, which will be in charge of dispatching these requests among the workers. Workers will send their replicate log through the PubSub messaging system to broadcast it to all other workers asynchronously:

At the end of our experiment, we will ask each of our workers for their individual version of the history of event (and to do so, our load balancer will also need to be able to list of all the workers) and make sure they agree.

A practical implementation of absurdity

We now have a stupid task to do, and a perfect architecture to do it. We just miss the perfect language for the task: Elixir.

A word on Elixir

Elixir is a dynamically typed functional programming language built on top of BEAM, the virtual machine of Erlang. Thanks to this, it inherits from the powerful capabilities of Erlang and its actor model in terms of fault tolerance and parallelism.

Elixir also have a strong similitude with Clojure. It puts the emphasis on being able to easily manipulate data rather than forcing data into types (I just wished it would have inherited from the amazing persistent vector of Clojure). It also has a powerful meta-programming model through macros.

Today, we will mostly use Elixir for its ability to easily instantiate actors, which will be of great help to build our distributed over-engineered sentence shuffling algorithm.

What is an actor?

We will let aside here the formal definition of actors (which is a really good read) and go straight to the implementation of actors in Elixir.

Actors are asynchronous independent light-weight processes, that each have their own state (and garbage collection), and can only communicate with other actors by sending messages or reacting to messages sent to them (in particular, actors cannot share state).

They are like objects (instances, not classes) that each run asynchronously and whose method calls are replaced by message passing. To “run a method”, we send a message containing the name of the method and the value of its arguments. To get back a result, we wait for an answer message.

The plan

We will now implement our random-shuffling workers as actors, maintaining a state of the event they know about, and communicating with the external world (such as other actors) through messages.

These worker actors will need to react to the following kind of messages:

- A

addmessage to insert of a new word in the data base - A

get_historymessage to retrieve the history of event as seen by the worker - A

replication_logmessage to transmit the replication log to others worker

Our worker actors will also need to emit replication_log messages (and not only react to them), as well as maintaining a logical clock to implement the Lamport timestamp algorithm.

Starting a worker

Our first task is to do what needs to be done to correctly instantiate new workers and initialize their state. The following code defines the equivalent of a constructor for an actor (*), the init method:

def init(_) do

PubSub.subscribe(@replication_log_topic, self())

{:ok, %State{ name: self(), clock: 1, eventLog: [] }}

end

The init method is called at the instantiation of an actor, to perform the appropriate side effects at initialization and return the initial state of the actor. In our case, at startup, our worker:

- Needs to subscribes to the replication log notifications (line 1)

- Init its state (line 2) with an logical clock starting at 1 and an empty event log

The event log represents what happened in the system, as viewed by the worker. Each log entry in this log contain the payload of an event, tagged with the time at which the event was processed, and its origin (where it was first processed). Here is the Elixir data type corresponding to a LogEntry:

defmodule LogEntry do

defstruct origin: nil, time: 0, event: nil

end

(*) In fact, this is the method used to initialize the state of a specific kind of actors, GenServers. This detail is not relevant here, but you are encouraged to follow the Elixir tutorial or the Erlang docs for more information.

Note: There is actually more logic to be done in the constructor, like getting the old history back (if a worker pops after events started flowing). We skipped this here for simplicity.

Querying for the history

Now that we are able to instantiate an actor, let us see how we can communicate with it. As seen earlier, actors can only communicate by sending messages to each other.

To handle and answer a given request in a actor, we need to implement a given callback (*) for this type of message. Technically, here is the code we need to react to the get_history message:

def handle_call(:get_history, _from, worker) do

sortedLog = Enum.sort_by(worker.eventLog, fn event -> {event.time, event.origin} end)

{:reply, sortedLog, worker}

end

Let’s take it step by step. First, the prototype. The function handle_call is the name of the callback we must implement, and it takes 3 parameters:

def handle_call(:get_history, _from, worker) do

…

end

- The message received: here we pattern match on the

:get_historyconstant - The origin of the message: the argument named

_from - The state of the actor at reception of the message: the argument named

worker

Now let us look at the content of the function. We recognize the Lamport timestamp total ordering we talked about earlier: the history of event is obtained by sorting the event log by time and then origin.

sortedLog = Enum.sort_by(worker.eventLog, fn event -> {event.time, event.origin} end)

The callback handle_call must then return a tuple of 3 elements (the last line of a function is always the returned piece of data of a function):

{:reply, sortedLog, worker}

- At the first position: whether or not the message was successfully handled (

:okfor success) - As the second position: the answer to the request, the sorted event log

- As the third position: the new state of the worker, which we keep unchanged here

Assembled together, this callback will make our workers react to the get_history message by answering a sorted event log (the history as the worker sees it), and keep the state of the actor unchanged.

(*) There are three main callbacks in a GenServer actor, named handle_call, handle_cast, and handle_info. handle_call is for synchronous requests, those for which the caller expects an answer.

Receiving events

To handle the insertion of a word of a sentence, we need to react to the add message. As before, we need to implement handle_call, but this time pattern matching on a message starting with the constant :add and containing a word as a payload:

def handle_call({:add, event}, _from, worker) do

logEntry = %LogEntry{

origin: worker.name,

time: worker.clock,

event: event

}

newWorkerState = %{ worker |

clock: worker.clock + 1,

eventLog: [logEntry | worker.eventLog]

}

PubSub.broadcast(@log_replication_topic, {:replication_log, logEntry})

{:reply, :ok, newWorkerState }

end

There are three main parts in this function. First we create a new log entry for the event we just received, tagged with the worker clock and the worker name:

logEntry = %LogEntry{

origin: worker.name,

time: worker.clock,

event: event

}

Then we construct the new worker state by appending the new entry in the log, and incrementing the logical clock of the worker by one:

newWorkerState = %{ worker | # Update worker state

clock: worker.clock + 1, # – increment clock by one

eventLog: [logEntry | worker.eventLog] # – prepend log entry to event log

}

Finally, we broadcast this new log entry to all other workers, before answering positively (:ok for success) to the request:

PubSub.broadcast(@log_replication_topic, {:replication_log, logEntry})

Receiving logs

Now for our last message, the replication log message. This time, we have to catch messages starting with :replication_log and containing a log entry payload:

def handle_info({:replication_log, logEntry}, worker) do

newWorkerState =

if logEntry.origin == worker.name do

worker

else

%{ worker |

clock: max(worker.clock, logEntry.time) + 1,

eventLog: [logEntry | worker.eventLog] }

end

{:noreply, newWorkerState }

end

Because we use a broadcast for the replication log, this function first has to check whether or not the worker is in fact the emitter of the replication log (logEntry.origin == worker.name).

In case the emitter is the receiver, the function does nothing. On the other hand, if the emitter is some other worker, it implements the Lamport timestamp logic:

%{ worker |

clock: max(worker.clock, logEntry.time) + 1,

eventLog: [logEntry | worker.eventLog] }

- The replicated log entry is appended to the log of the worker

- The worker clock is updated according to Lamport timestamp’s algorithm

Note: The astute code reader might have noticed we used handle_info instead of handle_call. This is no mistake. I will refer you to the GenServer documentation regarding why it is so.

The remaining pieces of infrastructure

At this point, our worker is fully implemented, but for some technical details we skipped here for clarity. You can find the full code here if you are interested.

To run our tests, we only miss our Pub/Sub messaging infrastructure and our Load Balancer. Fortunately, Elixir has quite a good ecosystem and there are some high quality libraries available, such as Phoenix.PubSub. A few lines of code to wrap them (you can find the full code here) and we get our infrastructure for free.

The whole project is available on GitHub.

Testing eventual stupidity

All of this work has not been in vain: it is now time to test our eccentric shuffling algorithm.

Example of random shuffling

Here is an example of sorted event log I got after sending the words of the sentence “hello my dear friend how are you in this glorious and beautiful day ?” to our eccentric shuffling algorithm:

[

%Worker.LogEntry{event: "friend", origin: #PID<0.183.0>, time: 1},

%Worker.LogEntry{event: "dear", origin: #PID<0.184.0>, time: 1},

%Worker.LogEntry{event: "my", origin: #PID<0.185.0>, time: 1},

%Worker.LogEntry{event: "hello", origin: #PID<0.186.0>, time: 1},

%Worker.LogEntry{event: "how", origin: #PID<0.186.0>, time: 5},

%Worker.LogEntry{event: "are", origin: #PID<0.185.0>, time: 6},

%Worker.LogEntry{event: "in", origin: #PID<0.183.0>, time: 7},

%Worker.LogEntry{event: "you", origin: #PID<0.184.0>, time: 7},

%Worker.LogEntry{event: "glorious", origin: #PID<0.185.0>, time: 9},

%Worker.LogEntry{event: "this", origin: #PID<0.186.0>, time: 9},

%Worker.LogEntry{event: "beautiful", origin: #PID<0.183.0>, time: 11},

%Worker.LogEntry{event: "and", origin: #PID<0.184.0>, time: 11},

%Worker.LogEntry{event: "today", origin: #PID<0.186.0>, time: 12},

%Worker.LogEntry{event: "?", origin: #PID<0.185.0>, time: 14}

]

In other words, all workers ended up agreeing on this random shuffling:

“friend dear my hello how are in you glorious this beautiful and day ?”

This, of course, is just one example of random shuffling of our original sentence. You can test other example by yourself: the code is available in GitHub.

The fascinating bit

What is interesting (and fascinating for me) is that, whatever the random order we end up having, all the workers will eventually always agree on the same. In fact, we can even write unit tests on it, and it will be green:

Eventually.assertUntil 100, 5, fn() ->

same_history =

Dispatcher.get_workers()

|> Enum.map(fn w -> Worker.get_history(w) end)

|> all_equal

assert same_history == true

end

We therefore managed to build a buzzword compliant, distributed sentence shuffling algorithm, all based on Lamport timestamp algorithm. Amazing, right?

Conclusion and what to read next

Beside having some random fun, I hope this post gave you the desire to read the original publication of Lamport: Time, Clocks, and the Ordering of Events in a Distributed System, which is truly an amazing paper to read.

This notion of ordering is obviously quite useful in distributed systems. For instance, generalizations of Lamport clocks, such as vector clocks, allow to identify concurrent modifications in a distributed systems, which is tremendously useful to resolve write conflicts (although they are not without problems).

The paper also shows an interesting application of Lamport timestamps, to implement a replicated state machine. This limited consensus algorithm is not fault tolerant (and is completely supplanted by algorithms such as Zookeeper Atomic Broadcast or Raft) but nevertheless quite smart and interesting to read.

Read this paper, try Elixir as well, you won’t regret it.

Comments