Statistical gender bias

I recently stumbled on a debate where Jordan B. Peterson argues, based on a statistical argument, that the gender pay gap is mostly not due to gender bias. Let’s see what’s wrong with this statistical argument.

The argument as I understood it

The host interviewing Jordan B. Peterson intially mentions around minute 5:55 that the gender pay gap in the UK is around 9% between men and women (women are payed 9% less).

Jordan B. Peterson answers that the gap this is not due to gender bias alone. To him, gender bias is only one of the causes and does only account for a fraction of the gender pay gap (minute 7:21).

He argues that, although there definitely a 9% pay gap between men and women, concluding this is only due to gender bias is too simplisitic. He argues that we need to perform a multi-variate analysis (with more than just 2 factors pay and gender) and look at the influence of the different factors.

He then affirms that if we do this, we can see that the other factors (which are correlated with behing a woman) explain this pay gap and that the gender bias itself only explain a fraction of the pay gap.

He takes the example of the agreable-ness personality trait, which encompasses being compassionate and polite. His argument is that because women are more agreeable, they are not asking for pay raise as often as men do, and are getting a lower wages in the end. He estimates this accounts for 5% of the pay gap.

He concludes that traits such as agreable-ness are causes of the gender pay gap, perhaps more so that the gender bias itself, which he thinks is actually much less than 9%.

Does this argument makes sense from a statistical point of view?

Asked different, to the extreme where the multivariate analysis would show that 100% of the pay gap can be “explained” by the “agreable” trait, would that means that gender bias does not exist?

What’s wrong with the argument?

The issue with the argument lies with the multi-variate analysis itself. What kind of analysis is being done is undefined in this talk but we might presume some kind of multivariate linear regression. Whatever the analysis itself, let’s see why it cannot help conclude that gender bias is not the core issue.

“Explain” does not mean “cause”

Statistical models can only tell you about correlation and not causation. In addition to that, statistically models will usually pick on the “simplest explanation” based on their expressiveness (their representational power).

Here is one typical example that is often used in Machine Learning communities, camel and cows:

- Camels are most often photographed with a desert background

- Cows are most often photographed with a grass background

Because it is very easy to discriminate on background colors and texture rather than shape, typical machine learning algorithms will “explain” the cow-ness or camel-ness of the photo (the observation) based on the background.

Does that means that, even if cows are always on grass and camel always in the desert, that the background determines the animal? Of course not! But statistical techniques will unfortunately pick up on that: when you present them with a cow in the desert, most models will likely answer “camel”.

An arbitrary causal model

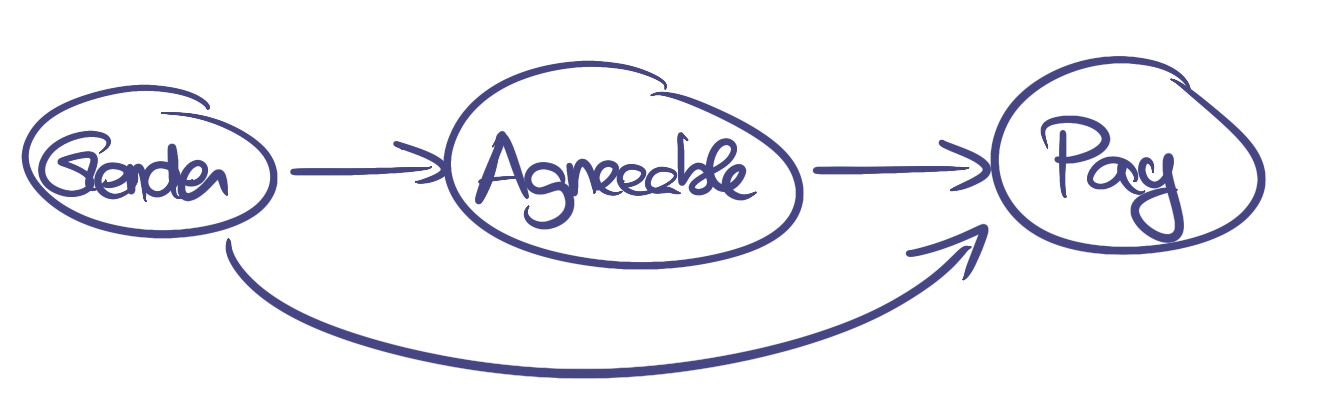

To make claims like Jordan B. Peterson does, you need a causal model. Here is the causal model that Jordan B. Peterson proposes during the debate, consisting of two factors:

- “Gender” between 0 and 1 (both included): 0 means being looking 100% masculine, and 1 means looking 100% feminine.

- “Agreeable” between 0 and 1 (both included): 0 means not being agreable at all and 1 means being 100% agreable.

In short, gender influence being agreable-ness. Both factors influence the pay.

But causal models like this cannot be tested by just observational data. You would need something like interventions to test the model: for instance modify the agreable-ness of a person and measure the influence of the pay.

Without such intervention, this causal model has no more value than any causal model that we could propose (adding / deleting / inversing arrows, etc).

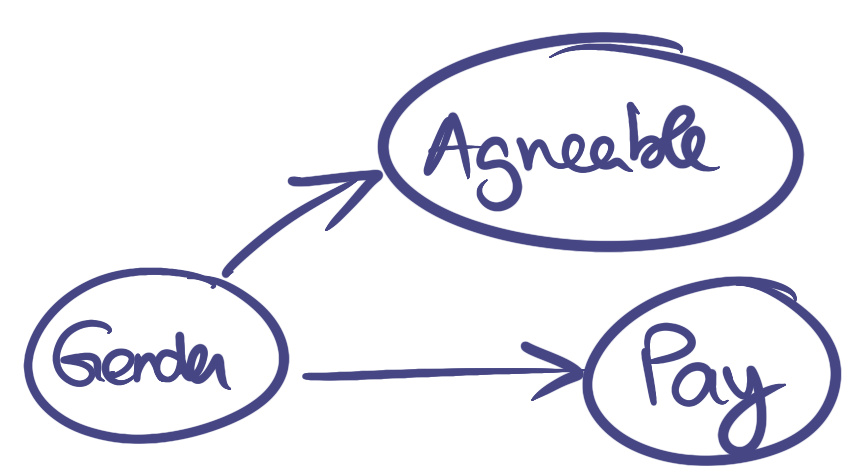

To see why, let’s propose a different model.

Radically different models can fit the same data

Here is a different causal model than the one proposed by Jordan B. Peterson. In this causal diagram, the agreable-ness is a side effect of the gender that has no direct influence on the pay:

Now, what’s interesting is that both causal diagrams displayed until now are completely undistinguishable with just observational data. Let’s show this by plugging some numbers in those causal diagrams:

Put whatever number you want as gender $g$ and we get the same values for agreeable-ness $a$ and pay $p$.

In other words, you could learn the coefficient of one model even if the data was generated from the other model, and fit both models perfectly to the same observational data.

Those two models are thus basically undistinguishable with just observational data… but lead to very different conclusions!

Time makes conclusion even more complex

Everything we discussed so far is in the context of static models: the causal model is unchanged as time passes. But change is the only constant: things are even more complex in practice!

We know for certainty that gender bias was huge just a few decades ago: plenty of countries did not even gave vote to women before the second world war… It is very likely that this gender bias persists through education and is behind the agreeable-ness between a trait more associated to women.

Here is one possible way it happened: women were seen as inferior as men and educated to be agreeable to men because they were taught men were superior. And now, the prejudice against women, abolished by law, is hidden behind the numbers on the diagram 1 above.

If that’s the case, the causal diagram today may look like Jordan B. Peterson causal diagram, but the main cause of gender pay gap remains gender bias: the factor behind the arrows might just be a matter of gender biased education.

The conclusion is in the eyes of the beholder

When dealing with observational data, causality is not achievable. In the absence of interventions, it is impossible to distinguish against multiple causal diagrams with just data.

In such instances, interpretation such as the one Jordan B. Peterson draws, are not strongly supported: they might agree with the data, but agreeing with the data is not enough as other models will do as well.

In such cases, any conclusion we make based on the data actually only shows our own preconceptions on what the causal model should be (we might be blinded by our own convictions, or prefer one conclusion to another) and does not make our conclusion valid.

Comments